Both finalists for NASA's next exploration mission have UA ties

NASA has selected a team that includes two University of Arizona planetary scientists as one of the two finalists to lead the next robotic solar system exploration mission.

“It was a nice Christmas gift,” said team member Thomas Zega, a UA associate professor of planetary science.

Also, the competing team is led by Elizabeth Turtle, who earned her Ph.D. at the UA in 1998 and is now a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

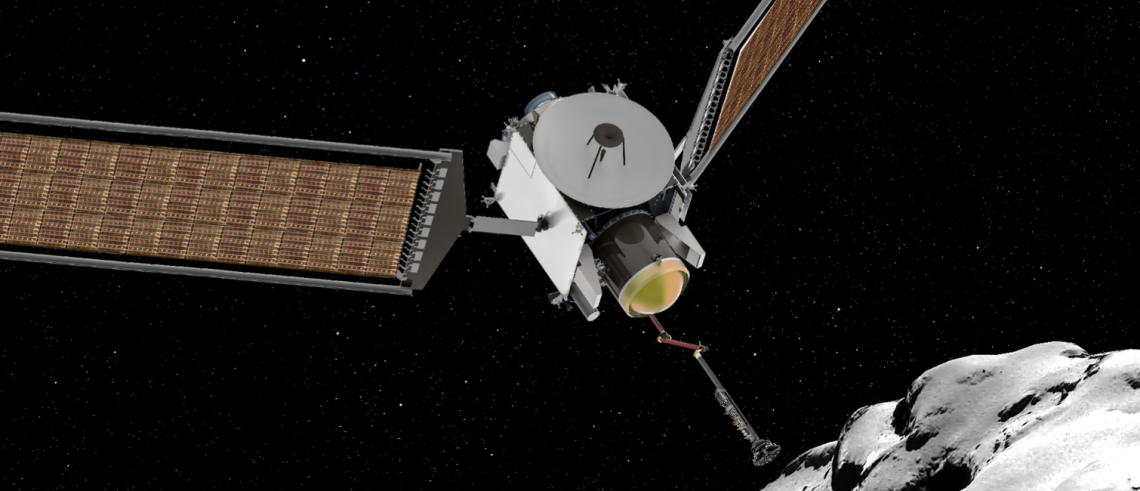

The UA-involved mission that caught NASA’s eye, called CAESAR for Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return, proposes to send a medium-sized spacecraft to a comet, snag a small sample and return it to Earth for analysis.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because the UA is leading the OSIRIS-REx mission to the asteroid Bennu to complete a similar mission.

Both Zega, an OSIRIS-REx collaborator, and Dante Lauretta, the OSIRIS-REx principal investigator, will participate in sample analysis.

The CAESAR team is led by Cornell University’s Steven Squyers, the principal investigator for the Spirit and Opportunity rovers on Mars, and managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

The two hope to use experience gleaned from OSIRIS-REx on CAESAR.

“The work done on CAESAR will ensure that the UA continues to stand at the forefront of extraterrestrial sample analysis for the next 20 years,” Lauretta said in a statement.

So why visit a comet if we are already asteroid-bound?

They are different creatures that could tell us different stories .

Asteroids are small, rocky bodies usually found between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Most of what we know about asteroids, we’ve learned from pieces of them that fall to Earth, called meteorites.

“We have to make heads or tails of the stuff that falls from the sky. The meteorites that we look at have been melted in their past, others don’t have that characteristic,” Zega said. It’s a hit or miss and many have unknown origins and histories.

Comets, on the other hand, are made mostly of dust and ice collected from the region beyond the gas giants, called the Kuiper Belt.

Comets are like a “cold-storage locker,” preserving the ingredients from the birth of the solar system, Zega said. “We don’t think the comet has been significantly altered since the solar system was put together.”

Further investigation of comets can also help answer the question of where the water on Earth came from. Some argue that it was brought here by colliding comets.

“But water is different on this comet, so if you’re interested in astrobiological implications and how the essentials for life got here, then missions like CAESAR are really important,” Zega said.

Planetary scientists have examined samples from the moon, other planets, meteorites and comet comas — the gaseous envelope. Even interplanetary dust particles can’t escape NASA’s scrutiny as they rain down on Earth from space — NASA collects those dust particles on special sticky sheets on aircraft flying through Earth’s stratosphere.

“We want to know the comet’s origin, history and compare it to measurements of other planetary samples we have,” Zega said. “The point of the mission is we know the source of our sample, we don’t know specifically where meteorites (or interplanetary dust particles) come from.”

The European Space Agency visited the targeted comet, 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, in 2014 as part of the Rosetta mission.

The surface was mapped and studied — a good reason to return.

“The Rosetta mission provided a base level of knowledge that we can use to design a very successful sample return,” Zega said.

The CAESAR team has been planning this mission for four years. Now, NASA will fund both finalists for a year to flesh out the mission details from beginning to end.

The competing mission, Dragonfly, has another target in mind. It was designed to have two stacks of four dome-like propellers to fly between undetermined sites where it will examine the chemistry of Saturn’s methane-ocean moon, Titan.

NASA will make a final decision in 2019.

If CAESAR is chosen, it could launch by 2025 and return to Earth by 2038.

“It would be a nice capstone to a career,” Zega said.

The chosen mission will receive $1 billion to execute the fourth iteration of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which was preceded by the Juno mission to Jupiter, the New Horizons flyby of Pluto and OSIRIS-REx.