By Daniel Stolte, University Communications - Aug. 16, 2017

Asked about her favorite planet in the solar system, Adriana Mitchell responds without hesitation: "Earth."

What about Mars? "Mars is very interesting, too," she says. "I hope to go there someday, actually."

And the way she says that, somehow, leaves no room for doubt.

Mitchell, an undergraduate student at the University of Arizona who majors in optical sciences and engineering, will start her junior year at the UA this fall. But while many of her peers are busy moving into residence halls and ordering textbooks, she is getting ready to start the first day of classes pointing a telescope outfitted with a polarimeter at the sun.

On Monday, Aug. 21, while the moon glides in front of the sun's blinding disc of light, Mitchell will focus her attention on an unprecedented effort to help solve some of the mysteries surrounding our home star. The mysteries are many, which is surprising if one considers that our species has looked up to, and studied, the sun ever since the first humans roamed the planet.

"One of the big questions in solar physics is: Why is the sun's corona hotter than the surface?" Mitchell says. "Or: Why does the solar wind accelerate dramatically as it streams out, going from one mile per second to a hundred?"

To pursue answers to some of these questions, Mitchell plays an important part in the most ambitious citizen science projects ever done during a total solar eclipse: the Continental-America Telescopic Eclipse Experiment, or Citizen CATE for short, a research project supported by federal, private and corporate contributions.

Passing the Torch

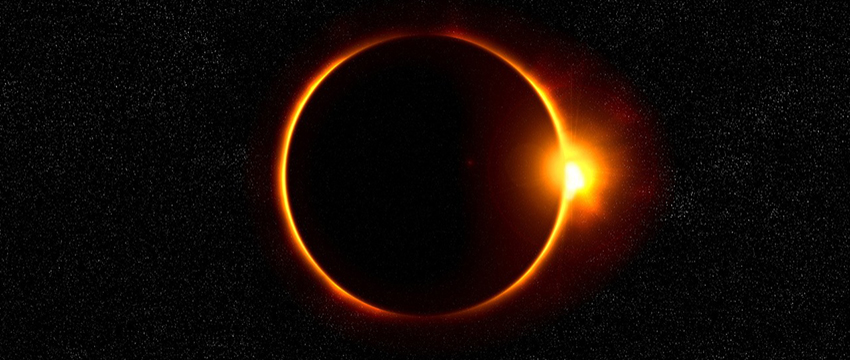

Sixty-eight telescopes, lined up like beads on a string along the path of totality, will be linked together to generate the longest movie of a solar eclipse ever made, resulting in 90 minutes of totality. To an observer within that path, the slowly moving moon will occult the sun for a maximum of two and a half minutes, before the famous "diamond ring" shape — the anticipated highlight for any eclipse chaser — announces the end of totality.

"We'll be passing the torch of collecting data all across the continent," explains Mitchell, who has been busy for more than a year readying science equipment, all to make sure everything goes smoothly during a natural spectacle that doesn't offer much opportunity for dress rehearsals.

CATE brings together volunteers from high schools, universities, informal education groups, astronomy clubs across the country, national science research labs and five corporate sponsors. Together, they will attempt what not even spacecraft dedicated to studying the sun have accomplished: to produce the first dataset of high-resolution, rapid-sequence, white-light images of the sun's inner corona over 90 minutes. The corona refers to a region of the solar atmosphere that typically is very challenging to image.

"The Earth and sun are intimately connected with the solar wind," says Matthew Penn, an astronomer at the National Solar Observatory, or NSO, in Tucson and CATE's principal investigator, who hired Mitchell in early 2016 to help get the project ready for the big moment. "This stream of particles blows through the entire solar system, and on bad days it can interfere with satellites and disrupt communications. With CATE, we want to better understand the sun's corona so we can better predict the solar wind."

For reasons physical and technical, even spacecraft can't observe the regions of the sun's corona that are closer to the star's surface than a little over one sun's diameter. And coronagraphs — devices placed in front of telescopes that block out the blinding glare — create issues by blurring the edges of the image. That is why scientists get so excited about the eclipse: When the moon moves into the path between Earth and sun, it functions as a distant, natural coronagraph that makes for much better observing conditions.

What Milkshakes Say About Solar Wind

With the string of telescopes operated by CATE volunteers, scientists such as Penn hope to measure the solar wind streaming out from the sun. Mitchell will perform a special and critical role during these observations, as she will operate one of only two sites where telescopes are outfitted with polarimeters, specialized filters that see only light waves that are synchronized in one plane. This allows them to track the so-called polar plumes, blobs of gas hurled from the sun's surface into space.

"It's a bit like sitting across the table from someone slurping a milkshake through a straw," Penn explains. "If you look closely, you'll see blobs of milkshake moving up the straw. By tracking those blobs of hot gas streaming from the sun and measuring their velocity, we can find out which of the models that solar physicists have proposed is correct."

Because safety is a critical part of the project, the sun's antics will be visible only to the cameras attached to the telescopes.

"Our telescopes don't have eyepieces," Mitchell says. "Looking into the sun through a telescope would immediately burn your retina. We want to make sure nobody gets injured."

Long before embarking to her site of study in Carbondale, Illinois, Mitchell was busy at the NSO, located across the street from the UA's Steward Observatory. To make sure that CATE's army of telescopes marches to the same beat, her duties included preparing truckloads — literally — of equipment.

"Everything was coming through Tucson," she says. "We got all this equipment, and we were setting up what seemed like a million computers. I remember all that stuff being in a room, and everything going like 'beep-beep-beep-beep' all day."

In practice runs conducted during a total eclipse in Indonesia in 2016, several sites unfortunately had their telescopes out of focus. Mitchell worked closely with a programmer from one of CATE's sponsoring companies to develop a way to make sure that wouldn't happen this time.

"This is actually more difficult than it sounds," Penn says. "In our recent practice runs, all of our volunteer groups have images that are in focus, due in a large part to Adriana's efforts."

"It's all automated," Mitchell says. "To capture the totality, all the volunteers have to do is push a start button and a stop button."

Getting Ready for 2024

When Mitchell isn't programming computers or adjusting telescope control motors, she brings her passion for science to the public. In June, Penn flew Mitchell out to Boulder, Colorado, to present the project during a national press conference about the eclipse.

"Adriana is a very talented undergraduate student," Penn says. "Her involvement in the project, which is really just something she's done on her own, has been remarkable. In addition to presenting poster papers at national meetings and being a co-author on our science papers, she is the best public speaker that I have among the students in the program."

Because all sites involved in CATE get to keep their telescopes after the eclipse, the project's scientists already are hatching plans about what they should set their sights on next.

"We're thinking about short-lived targets like comet flybys or the brightness fluctuations in variable stars," Mitchell says, "anything that would benefit from observing with multiple telescopes spread out over large areas."

"There is another solar eclipse coming up in 2024," Penn says, "and ideally we'd like to have polarimeters set up along the path of totality for that one."

By that time, Mitchell, may already have a Ph.D.

"I'm definitely going to grad school," she says. "Since I'm mostly interested in planetary science, I'd like to build instruments. Like an infrared imager or some type of spectrometer that could someday fly through the geysers on Saturn's moon Enceladus. That would be really cool."

The way Adriana Mitchell says that, somehow, leaves no room for doubt.