The OSIRIS-REx mission was highlighted in the Spring 2013 edition of Arizona, the UA alumni magazine, with a suite of six articles featuring Professor Dante Lauretta and some of the UA students (graduate and undergraduate) working on the mission project.

OSIRIS-REx Mission: Are We Stardust?

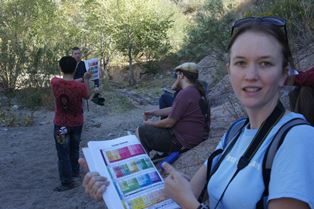

OSIRIS-REx Students

A Scientist, Runner, and Musician Pulls an Intricate Camera System Together - on Deadline

A Sophomore Writes Code to Track a NASA Robot

An Engineer - and his Dog - Settle In To Make History

Sarah Mattson, Senior Staff Technician with the

Sarah Mattson, Senior Staff Technician with the